“On Artemis III, we anticipate using at least two of the launch sites: one at KSC and one at Starbase.”

There are a couple of ways to read the announcement from the Federal Aviation Administration that it’s kicking off a new environmental review of SpaceX’s plan to launch the most powerful rocket in the world from Florida.

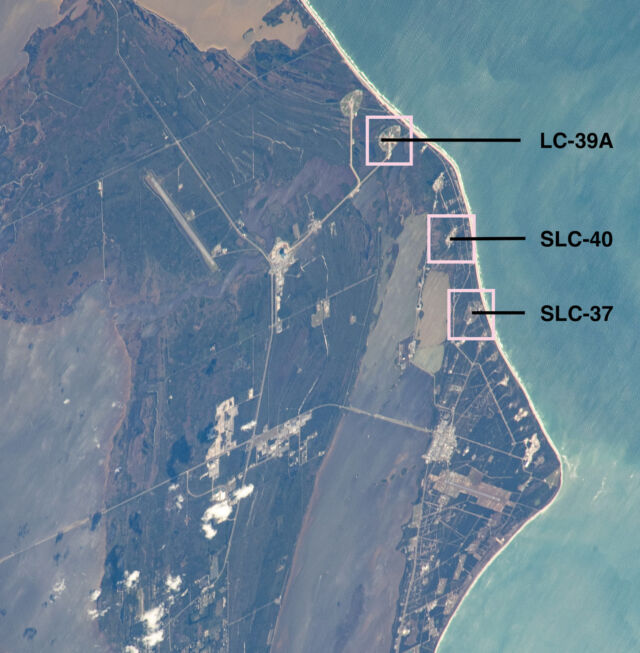

The FAA said on May 10 that it plans to develop an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for SpaceX’s proposal to launch Starships from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The FAA ordered this review after SpaceX updated the regulatory agency on the projected Starship launch rate and the design of the ground infrastructure needed at Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A), the historic launch pad once used for Apollo and Space Shuttle missions.

Dual environmental reviews

At the same time, the US Space Force is overseeing a similar EIS for SpaceX’s proposal to take over a launch pad at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, a few miles south of LC-39A. This launch pad, designated Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37), is available for use after United Launch Alliance’s last Delta rocket lifted off there in April.

On the one hand, these environmental reviews often take a while and could cloud Elon Musk’s goal of having Starship launch sites in Florida ready for service by the end of 2025. “A couple of years would not be a surprise,” said George Nield, an aerospace industry consultant and former head of the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation.

Another way to look at the recent FAA and Space Force announcements of pending environmental reviews is that SpaceX finally appears to be cementing its plans to launch Starship from Florida. These plans have changed quite a bit in the last five years.

The environmental reviews will culminate in a decision on whether to approve SpaceX’s proposals for Starship launches at LC-39A and SLC-37. The FAA will then go through a separate licensing process, similar to the framework used to license the first three Starship test launches from South Texas.Advertisement

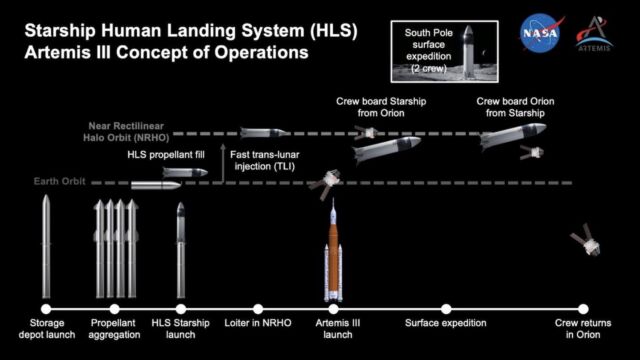

NASA has contracts with SpaceX worth more than $4 billion to develop a human-rated version of Starship to land astronauts on the Moon on the first two Artemis lunar landing flights later this decade. To do that, SpaceX must stage a fuel depot in low-Earth orbit to refuel the Starship lunar lander before it heads for the Moon. It will take a series of Starship tanker flights—perhaps 10 to 15—to fill the depot with cryogenic propellants.

Launching that many Starships over the course of a month or two will require SpaceX to alternate between at least two launch pads. NASA and SpaceX officials say the best way to do this is by launching Starships from one pad in Texas and another in Florida.

Earlier this week, Ars spoke with Lisa Watson-Morgan, who manages NASA’s human-rated lunar lander program. She was at Kennedy Space Center this week for briefings on the Starship lander and a competing lander from Blue Origin. One of the topics, she said, was the FAA’s new environmental review before Starship can launch from LC-39A.

“I would say we’re doing all we can to pull the schedule to where it needs to be, and we are working with SpaceX to make sure that their timeline, the EIS timeline, and NASA’s all work in parallel as much as we can to achieve our objectives,” she said. “When you’re writing it down on paper just as it is, it looks like there could be some tight areas, but I would say we’re collectively working through it.”

Officially, SpaceX plans to perform a dress rehearsal for the Starship lunar landing in late 2025. This will be a full demonstration, with refueling missions, an uncrewed landing of Starship on the lunar surface, then a takeoff from the Moon, before NASA commits to putting people on Starship on the Artemis III mission, currently slated for September 2026.

So you can see that schedules are already tight for the Starship lunar landing demonstration if SpaceX activates launch pads in Florida late next year.

ARS VIDEO

How The Callisto Protocol’s Gameplay Was Perfected Months Before Release

Let’s be real

While the environmental review may not be welcome news for SpaceX, let’s be real for a moment. The company has a lot of work to do before Starship can reach the Moon. First and foremost, Watson-Morgan said NASA wants to see SpaceX string together dozens of Starship launches with reliable performance from the rocket’s methane-fueled engines. SpaceX must also prove it can refuel Starship in orbit and create a a hospitable crew cabin for astronauts.

These are serious engineering problems that will take time to solve, but SpaceX’s track record suggests its engineers can solve them. SpaceX also needs time to actually build the new Starship launch pads. While the skeleton of a Starship launch tower is in place at LC-39A, the site doesn’t yet have any of the propellant storage or fueling infrastructure needed for launch operations.

SpaceX’s portion of the Artemis program, while significant, is just one piece of the puzzle. Axiom Space, another NASA contractor, must complete the development of a new spacesuit before astronauts make the first Artemis lunar landing. There’s no assurance that NASA’s chronically delayed Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft, which will ferry astronauts to the vicinity of the Moon to meet up with the Starship lander, will be ready for a lunar landing mission in the next few years.

The schedule for the Artemis III lunar landing in 2026 seems completely unrealistic, which has prompted NASA officials to consider revamping the flight plan for Artemis III to have an Orion crew capsule dock with Starship in low-Earth orbit. This would be achievable well before a lunar landing mission, allowing NASA and SpaceX to reduce risk for the later Moon flight and close a potential years-long gap between Artemis missions, which could threaten political support for the program.

There is widespread agreement among government and industry officials that the FAA’s commercial space office is underfunded to meet the demands of the rapidly growing space industry. Last fall, SpaceX called for Congress to add money to the FAA’s budget to double the staff of the commercial space office. The FAA is charged with ensuring public safety during commercial rocket launches, along with compliance with environmental laws.Advertisement

“The fact that it can take years to go through this process is not a good thing in terms of how fast commercial space and other activities would like to be able to go,” Nield said.

Last fall, a SpaceX official told Ars that FAA licensing was a “critical path item for the Artemis program.” Before the second Starship test flight last November, SpaceX waited a couple of months for the FAA to issue a launch license.

“In terms of timing, yes, environmental reviews can often be the long pole,” Nield said. “I don’t think this will end up being the critical factor in the schedule for Artemis missions.”

Let’s imagine a scenario in which SpaceX has proven it can refuel Starship in orbit and has completed an uncrewed landing on the Moon, and the spacesuits, the SLS rocket, and Orion spacecraft are ready for a lunar landing mission. But what if SpaceX lacks FAA approval to launch Starship from Florida or runs into lengthy construction delays?

In that scenario, Watson-Morgan said it’s “conceivable” that SpaceX could launch all of the Starship tanker and depot missions from two launch pads in Texas. “But that is not the current plan,” she said. “The plan is to have LC-39A at KSC up and operational. SpaceX is kind of a just-in-time, rapid-iteration-type company, so they are focused right now on the pads at Starbase.”

“There are different ways you could do this, and SpaceX has a history of moving pretty fast in putting together places to operate, so we’ll see how that comes out,” Nield said. “There are a lot of things that have to happen right in order to meet the kinds of schedules that people are aiming toward.”

But for lunar landing campaigns, NASA’s preference is clearly to cycle between Starship launches in Texas and Florida.

“On Artemis III, we anticipate using at least two of the launch sites: one at KSC and one at Starbase,” Watson-Morgan said.

Shifting plans at LC-39A

SpaceX signed a 20-year lease with NASA for LC-39A in 2014. Since then, the company has launched 83 missions from this pad since 2017 with its operational Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. Early last year, SpaceX reshaped the Cape Canaveral skyline by stacking a more than 450-foot-tall (137-meter) Starship launch tower about 1,000 feet (300 meters) from the existing Falcon 9 launch mount at LC-39A.

Then, seemingly as quickly as SpaceX put it up, work stalled on the new Starship launch tower for most of last year. Finally, in the last few months, some construction work has resumed at the site. The location of the Starship launch tower close to the existing Falcon 9 launch pad raised some concerns within NASA that an explosion could damage the only launch site capable of accommodating astronaut missions to the International Space Station. In response, SpaceX modified a nearby launch pad for crew and cargo missions.

At LC-39A, onlookers have spotted construction crews disassembling the legs already in place for the Starship launch mount. Presumably, SpaceX is redesigning the launch mount and modifying the foundation of the Starship pad for a water deluge system. These changes are based on lessons learned from Starship test flights from Texas.

NASA and SpaceX already completed an environmental assessment in 2019 for launching Starship from LC-39A. Since then, the full-scale Super Heavy booster and Starship rocket have launched three times from SpaceX’s Starbase facility located at Boca Chica Beach, Texas, just north of the US-Mexico border. A fourth test flight could happen at the end of May or early next month.

With Starship now flying, SpaceX has a better handle on how it will operate the rocket in Florida. In its notice announcing the pending environmental review, the FAA said SpaceX’s concept of operations has “evolved” since 2019. Rather than the previous estimate of 24 Starship launches per year at LC-39A, SpaceX now projects a higher tempo of up to 44 flights per year. SpaceX also proposes launching a more powerful version of the Super Heavy booster and Starship, with up to 35 engines on the first stage and up to nine engines on the upper stage, up from 31 and six.

“As they gain experience and start to firm up their plans, it looks like their planned launches don’t necessarily fall within that previous scenario,” Nield said. “So in terms of size, the exact location, and the launch frequency, that’s no longer being covered by the work that had been done previously. What that means is, at the very least, you need to go back and potentially modify the existing assessments.”

Construction on hold?

SpaceX plans to land the reusable Super Heavy first stage booster back at the launch site rather than downrange on a drone ship. To do this, the company wants to build a catch tower that will use articulating arms to grab onto the rocket as it slows to a hover just above the ground. This is a separate tower from the Starship launch pad structure currently in place at LC-39A. Other new facilities SpaceX wants to build at LC-39A include a natural gas liquefaction system, an air separation unit for propellant generation, and a water deluge system to dampen the force of liftoff.

It’s not clear how much of this construction can proceed while the FAA’s environmental review remains open. NASA said it has only provided approval for SpaceX to build Starship launch infrastructure at LC-39A that is within the scope of the 2019 environmental assessment.

“SpaceX, as a tenant leaseholder on Kennedy Space Center, is not authorized to undertake any construction activity at LC-39A related to Starship launch and landing facilities without prior approval from NASA,” NASA said in a statement to Ars. “This EIS will support future decision-making on, among other things, construction activities that may be proposed to occur at LC-39A.”

An EIS, like those underway at two sites in Florida, is the most thorough type of environmental review the FAA can undertake to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969. The EIS process takes longer than environmental assessments like the one NASA concluded in 2019 for SpaceX’s original proposal to launch Starship from LC-39A.

“In consideration of SpaceX’s proposal, NASA, as the land management agency, and the FAA, as the licensing agency, have determined that an EIS is the appropriate level (of review) to address the potential environmental impacts of Starship-Super Heavy operations at LC-39A,” a NASA spokesperson told Ars.

An FAA spokesperson said the agency expects to issue a draft version of the EIS for LC-39A sometime next year but didn’t provide a more specific timeline. This will be followed by a public comment period before the FAA publishes the final report and decides whether SpaceX can launch Starships out of LC-39A.

The Space Force projects that a similar ongoing environmental review at SLC-37 will take at least a year and a half. This review started early this year, so the estimated completion date is in September 2025. If the FAA’s review follows the same timeline, the end of 2025 seems like a best-case scenario for a decision on LC-39A.

However, Nield said the engineers, scientists, and regulators reviewing SpaceX’s proposal for LC-39A will have access to the results of the environmental assessment NASA completed in 2019.

“I think they’re in a much better position than starting from scratch,” he said. “At the same time, this is a much bigger effort that is being proposed now, so it’s not just a question of ‘let’s change this number to that, or we’ll broaden the number of plants or animals or fish or whatever that might be impacted.'”Advertisement

Where to build and launch

SpaceX’s iterative approach to designing and testing Starship centers on a spiral development model. Essentially, it’s a cycle of build, test, find, and fix, where SpaceX assembles a full-size Starship rocket, launches it, finds what went wrong, and then fixes the problems on the next rocket. For this model to work, the company must have a lot of rocket hardware on hand. SpaceX is expanding its sprawling campus of assembly buildings and high bays at Starbase, with several Starships well into production for future test flights. One of these buildings called the Starfactory, will spread across a million square feet to produce components for multiple Starships per week.

“This is now going to be a permanent location for us to be producing and launching vehicles,” said Kathy Lueders, SpaceX’s general manager at Starbase, in a talk earlier this week. SpaceX is also putting in an office building for SpaceX employees at Starbase.

“Then, we’ll probably be in the process of building another high bay,” she said. “We are building a second pad right now, too. All of this is to get us ready to be able to start meeting the production and launch rate that we need to be able to accomplish our missions.”

SpaceX eventually aims to launch Starships more often than it flies the Falcon 9 rocket, which has launched at an average cadence of once every 2.7 days since the start of the year. With design upgrades, a reusable Starship could deliver more than 100 metric tons of payload to low-Earth orbit.

Lueders said SpaceX has invested more than $3 billion at Starbase since 2014. The company is about to start construction of a second launch pad at Starbase next to the existing tower. More than 3,000 SpaceX employees and contractors work at Starbase every day, she said.

“We need two launch areas for us to be able to meet our manifest,” Lueders said. “Just a single (Moon) landing requires 15 tanker launches, and they need to be done within a certain period of time.”

In her remarks to local officials in South Texas, Lueders said Starbase will remain SpaceX’s “workhorse area” for Starship development and testing. Musk has said he envisions the Texas location as a research and development complex and Florida as an operational launch base.

“We will also need the Florida base to be able to do the number and sequencing of the missions. We’re trying to figure out how to do the mix,” Lueders said. “We’re still working through this but … we know Starbase is going to be the home of Starship.”

There’s currently no capacity to build Starships in Florida and no evidence of imminent construction of a Starship factory at Cape Canaveral.

The Cape Canaveral spaceport is a draw for almost every US launch company. Starship’s arrival will “unlock a lot more potential at places like Cape Canaveral that are already world leaders in terms of space launch,” said Rob Long, president and CEO of Space Florida, a state-backed enterprise established to attract aerospace business.

Eventually, SpaceX may build a rocket factory on Florida’s Space Coast, but if Starships are really going to launch from the Kennedy Space Center in the next couple of years, the company will need to ship the 30-foot-diameter (9-meter) vehicles from the factory in South Texas. Officials haven’t said how they will transport boosters and the ship 1,000 miles (1,600 km) across the Gulf of Mexico.Advertisement

Whatever SpaceX decides, Long said Cape Canaveral is uniquely positioned for Starship. With a deepwater seaport, air, road, and rail connections, plus access to space, the region is home to the nation’s only “quintemodal” port.

“I think that really leans into this thought of normalizing space launch as a true mode of transportation, just like air, land, or sea modes of transportation,” he said.

SpaceX’s shifting plans for Starship in Florida are not a big surprise to anyone who has watched the arc of the company’s development. At one time, SpaceX acquired oceangoing oil rigs to convert them into mobile launch and landing pads for Starship. For now, SpaceX has dropped that idea.

The three Starship test flights over the last year have each been valuable learning exercises, influencing design changes that SpaceX will incorporate into future launch pads. In that context, SpaceX’s decision to temporarily halt construction at LC-39A makes some sense.

SpaceX also abandoned a plan to build a Starship launch pad at an undeveloped site, known as Launch Complex 49 (LC-49), on the northern side of the Kennedy Space Center. In late 2021, NASA announced it was beginning the environmental assessment process for LC-49. Early this year, NASA said it suspended those plans.

Instead, SpaceX has proposed basing Starship flights at SLC-37, which sits on Space Force property. If SpaceX doesn’t get approval to launch there, it proposed a backup option of building a brand new launch pad called SLC-50 just north of SLC-37.

With two launch pads at Starbase, plus LC-39A and SLC-37 in Florida, SpaceX would have four active Starship launch pads. This should be enough to support the kind of Starship launch rate SpaceX needs to achieve through the rest of this decade for test flights, lunar missions supporting NASA’s Artemis program, and launches of Starlink broadband satellites.

Ultimately, if Musk’s grandest ambitions for a Mars settlement become real, SpaceX probably needs a lot more launch pads.