The space agency did consider alternatives to splashing the station.

NASA has awarded an $843 million contract to SpaceX to develop a “US Deorbit Vehicle.” This spacecraft will dock to the International Space Station in 2029 and then ensure the large facility makes a controlled reentry through Earth’s atmosphere before splashing into the ocean in 2030.

“Selecting a US Deorbit Vehicle for the International Space Station will help NASA and its international partners ensure a safe and responsible transition in low Earth orbit at the end of station operations,” said Ken Bowersox, NASA’s associate administrator for Space Operations, in a statement. “This decision also supports NASA’s plans for future commercial destinations and allows for the continued use of space near Earth.”

NASA has a couple of reasons for bringing the space station’s life to a close in 2030. Foremost among these is that the station is aging. Parts of it are now a quarter of a century old. There are cracks on the Russian segment of the space station that are spreading. Although the station could likely be maintained beyond 2030, it would require increasing amounts of crew time to keep flying the station safely.

Additionally, NASA is seeking to foster a commercial economy in low-Earth orbit. To that end, it is working with several private companies to develop commercial space stations that would be able to house NASA astronauts, as well as those from other countries and private citizens, by or before 2030. By setting an end date for the station’s lifetime and sticking with it, NASA can help those private companies raise money from investors.

ARS VIDEO

What Happens to the Developers When AI Can Code? | Ars Frontiers

Do we have to sink the station?

The station, the largest object humans have ever constructed in space, is too large to allow it to make an uncontrolled return to Earth. It has a mass of 450 metric tons and is about the size of an American football field. The threat to human life and property is too great. Hence the need for a deorbit vehicle.

The space agency considered alternatives to splashing the station down into a remote area of an ocean. One option involved moving the station into a stable parking orbit at 40,000 km above Earth, above geostationary orbit. However, the agency said this would require 3,900 m/s of delta-V, compared to the approximately 47 m/s of delta-V needed to deorbit the station. In terms of propellant, NASA estimated moving to a higher orbit would require 900 metric tons, or the equivalent of 150 to 250 cargo supply vehicles.

NASA also considered partially disassembling the station before its reentry but found this would be much more complex and risky than a controlled deorbit that kept the complex intact.

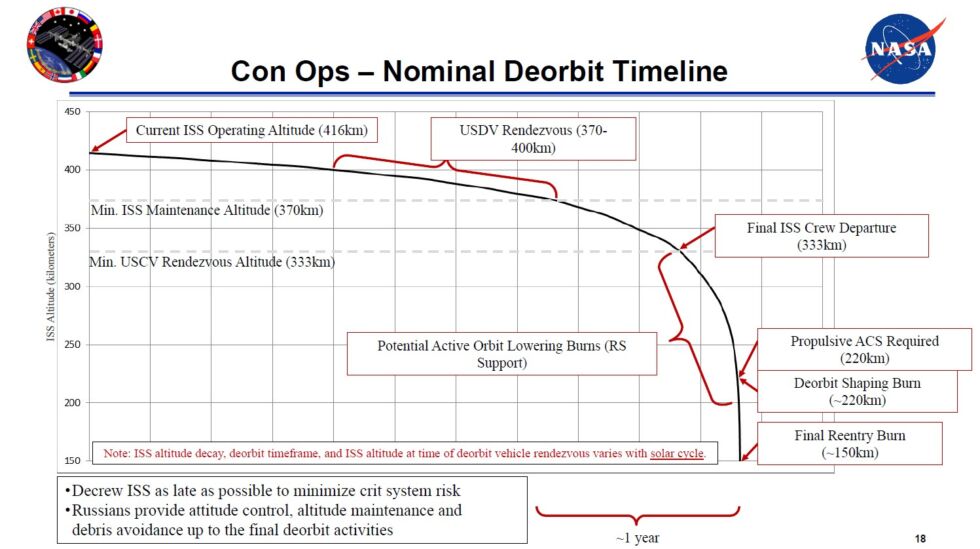

The NASA announcement did not specify what vehicle SpaceX would use to perform the deorbit burn, but we can draw some clues from the public documents for the contract procurement. For example, NASA will select a rocket for the mission at a later date, but probably no later than 2026. This would support a launch date in 2029, to have the deorbit vehicle docked to the station one year before the planned reentry.

How will they do it?

Because of the sensitivity of the mission, NASA is likely to require a “Category 3” rocket under the auspices of its Launch Services Program, which are rockets that have a robust launch history. The agency notes that some rockets that fit this category are SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket and Northrop Grumman’s Pegasus and Minotaur rockets. Because SpaceX is the contractor for the deorbit vehicle, it stands to reason that it likely will launch on a Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy. It’s possible that SpaceX bid Starship for this mission, although I think that is unlikely because the vehicle is not classified as a Category 3 rocket now, nor is it likely to be for at least a couple of years.

Without seeing SpaceX’s actual bid, it’s impossible to know what the company’s plan is. An unmodified Dragon 2 spacecraft would probably not have the propulsive capability to accomplish this task. At a minimum, it would require much larger propellant tanks, perhaps by significantly modifying the trunk.

Another option is the “Dragon XL” spacecraft, which SpaceX is designing to supply NASA’s Lunar Gateway station near the Moon. This vehicle could conceivably have the propulsive capability to deorbit the station, and, critically, it is being designed to have the capability to remain docked to a space station for 12 months or longer, similar to the requirement for the deorbit vehicle. Therefore, this seems like the most probable choice.

The bidding process for the US Deorbit Vehicle was opaque, but there are a few intriguing clues. Initially, the contract was offered as a hybrid. NASA’s original documents said the “design” portion of the contract would be cost-plus and the development portion firm-fixed-price. Then a couple of things happened. Perhaps because there were not that many bidders (one source suggested to Ars that SpaceX did not even bid initially), NASA modified the process to allow flexibility on the contracting mechanism. Then, earlier this year, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson estimated that the US Deorbit Vehicle would cost $1.5 billion.

This week’s announcement of a contract price came in well below that—indicating that the space agency got a better deal than Nelson anticipated. And notably, the award is entirely based on a firm-fixed-price contract, which is SpaceX’s preferred way of working with NASA.

“The contract is a single-award firm-fixed-price core with indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity, firm-fixed-price task orders,” NASA spokesman Joshua Finch told Ars on Wednesday night. “To maximize value to the government and enhance competition, the acquisition allowed offerors flexibility in proposing firm-fixed-price or a cost-plus incentive fee for the design, development, test and evaluation phase, as well as for the production, assembly, integration, and test phase.”