As AI deepfakes sow doubt in legitimate media, anyone can claim something didn’t happen.

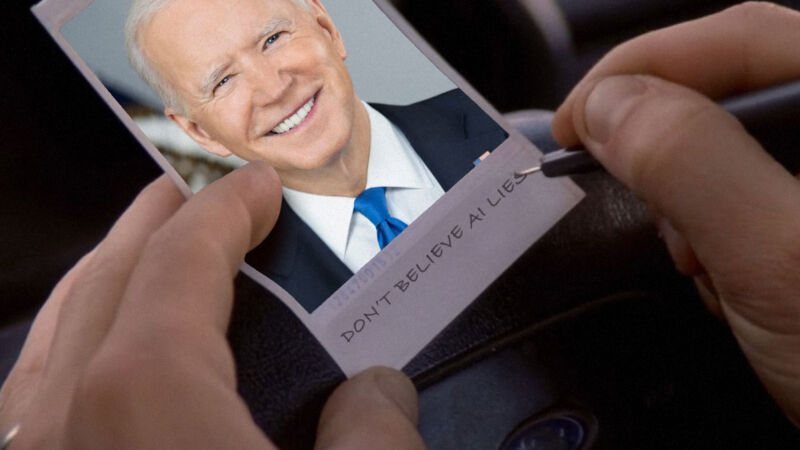

Given the flood of photorealistic AI-generated images washing over social media networks like X and Facebook these days, we’re seemingly entering a new age of media skepticism: the era of what I’m calling “deep doubt.” While questioning the authenticity of digital content stretches back decades—and analog media long before that—easy access to tools that generate convincing fake content has led to a new wave of liars using AI-generated scenes to deny real documentary evidence. Along the way, people’s existing skepticism toward online content from strangers may be reaching new heights.

Further Reading

The many, many signs that Kamala Harris’ rally crowds aren’t AI creations

Deep doubt is skepticism of real media that stems from the existence of generative AI. This manifests as broad public skepticism toward the veracity of media artifacts, which in turn leads to a notable consequence: People can now more credibly claim that real events did not happen and suggest that documentary evidence was fabricated using AI tools.

The concept behind “deep doubt” isn’t new, but its real-world impact is becoming increasingly apparent. Since the term “deepfake” first surfaced in 2017, we’ve seen a rapid evolution in AI-generated media capabilities. This has led to recent examples of deep doubt in action, such as conspiracy theorists claiming that President Joe Biden has been replaced by an AI-powered hologram and former President Donald Trump’s baseless accusation in August that Vice President Kamala Harris used AI to fake crowd sizes at her rallies. And on Friday, Trump cried “AI” again at a photo of him with E. Jean Carroll, a writer who successfully sued him for sexual assault, that contradicts his claim of never having met her.

Legal scholars Danielle K. Citron and Robert Chesney foresaw this trend years ago, coining the term “liar’s dividend” in 2019 to describe the consequence of deep doubt: deepfakes being weaponized by liars to discredit authentic evidence. But whereas deep doubt was once a hypothetical academic concept, it is now our reality.

Ars Video

How Scientists Respond to Science Deniers

The rise of deepfakes, the persistence of doubt

Doubt has been a political weapon since ancient times. This modern AI-fueled manifestation is just the latest evolution of a tactic where the seeds of uncertainty are sown to manipulate public opinion, undermine opponents, and hide the truth. AI is the newest refuge of liars.

Further Reading

AI image generation tech can now create life-wrecking deepfakes with ease

Over the past decade, the rise of deep-learning technology has made it increasingly easy for people to craft false or modified pictures, audio, text, or video that appear to be non-synthesized organic media. Deepfakes were named after a Reddit user going by the name “deepfakes,” who shared AI-faked pornography on the service, swapping out the face of a performer with the face of someone else who wasn’t part of the original recording.

In the 20th century, one could argue that a certain part of our trust in media produced by others was a result of how expensive and time-consuming it was, and the skill it required, to produce documentary images and films. Even texts required a great deal of time and skill. As the deep doubt phenomenon grows, it will erode this 20th-century media sensibility. But it will also affect our political discourse, legal systems, and even our shared understanding of historical events that rely on that media to function—we rely on others to get information about the world. From photorealistic images to pitch-perfect voice clones, our perception of what we consider “truth” in media will need recalibration.

In April, a panel of federal judges highlighted the potential for AI-generated deepfakes to not only introduce fake evidence but also cast doubt on genuine evidence in court trials. The concern emerged during a meeting of the US Judicial Conference’s Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, where the judges discussed the challenges of authenticating digital evidence in an era of increasingly sophisticated AI technology. Ultimately, the judges decided to postpone making any AI-related rule changes, but their meeting shows that the subject is already being considered by American judges.

Deep doubt impacts more than just current events and legal issues. In 2020, I wrote about a potential “cultural singularity,” a threshold where truth and fiction in media become indistinguishable. A key part of the threshold is the level of “noise,” or uncertainty, that AI-generated media can inject into our information ecosystem at scale. Deepfakes may lead to scenarios where the prevalence of AI-generated content could create widespread doubt about the authenticity of real events that took place in history—perhaps another manifestation of deep doubt. In 2022, Microsoft Chief Scientific Officer Eric Horvitz echoed these ideas when he wrote a research paper about a similar topic, warning of a potential “post-epistemic world, where fact cannot be distinguished from fiction.”

And deep doubt could erode social trust on a massive, Internet-wide scale. This erosion is already manifesting in online communities through phenomena like the growing conspiracy theory called “dead Internet theory,” which posits that the Internet now mostly consists of algorithmically generated content and bots that pretend to interact with it. The ease and scale with which AI models can now generate convincing fake content is reshaping our entire digital landscape, affecting billions of users and countless online interactions.

Deep doubt as “the liar’s dividend”

“Deep doubt” is a new term, but it’s not a new idea. The erosion of trust in online information from synthetic media extends back to the origins of deepfakes themselves. Writing for The Guardian in 2018, David Shariatmadari spoke of an upcoming “information apocalypse” due to deepfakes and questioned, “When a public figure claims the racist or sexist audio of them is simply fake, will we believe them?”

Further Reading

AI-generated puffy pontiff image inspires new warning from Pope Francis

In 2019, Danielle K. Citron of Boston University School of Law and Robert Chesney of the University of Texas, in a paper called “Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security,” coined the term “liar’s dividend” to describe this phenomenon. In that paper, the authors say that “deepfakes make it easier for liars to avoid accountability for things that are in fact true.”

This “liar’s dividend” paradoxically increases in efficacy as society becomes more educated about the dangers of deepfakes since they will know it is possible to fake various forms of media easily. The paper warns that this trend could exacerbate distrust in traditional news sources, potentially eroding the foundations of democratic discourse. Moreover, the authors suggest that the phenomenon could create fertile ground for authoritarianism, as objective truths lose their power and opinions become more influential than facts.

The concept of deep doubt also intersects with existing issues of misinformation and disinformation. It provides a new tool for those seeking to spread false narratives or attempting to discredit factual reporting. This could lead to the acceleration of the already present scenario, driven by cable news media and social media in particular, in which our shared cultural perception of “truth” becomes even more subjective, with more individuals choosing to believe what aligns with their preexisting views rather than considering the evidence from a different cultural perspective.

How to counter deep doubt: Context is key

All meaning derives from context. In a sense, crafting our own interrelated web of ideas is how we make sense of reality. Considering any idea standing alone without knowing how it links up conceptually with the existing world is meaningless. Along those lines, attempting to authenticate a potentially falsified media artifact in isolation doesn’t make much sense.

Throughout recorded history, historians and journalists have had to evaluate the reliability of sources based on provenance, context, and the messenger’s motives. For example, imagine a 17th-century parchment that apparently provides key evidence about a royal trial. To determine if it’s reliable, historians would evaluate the chain of custody, as well as check if other sources report the same information. They might also check the historical context to see if there is a contemporary historical record of that parchment existing. That requirement has not magically changed in the age of generative AI.

Further Reading

With Stable Diffusion, you may never believe what you see online again

In the face of growing concerns about AI-generated content, several tried-and-true media literacy strategies can help verify the authenticity of digital media, as Ars Technica’s Kyle Orland pointed out during our coverage of the Harris crowd-size episode.

When we are evaluating the veracity of online media, it’s important to rely on multiple corroborating sources, particularly those showing the same event from different angles in the case of visual media or reported from multiple credible sources in the case of text. It’s also useful to track down original reporting and imagery from verified accounts or official websites rather than trusting potentially modified screenshots circulating on social media. Information from varied eyewitness accounts and reputable news organizations can provide additional perspectives to help you look for logical inconsistencies between sources.

In general, we recommend approaching claims of AI manipulation skeptically, considering simpler explanations for unusual elements in media before jumping to conclusions about AI involvement, which may fit a satisfying narrative (through confirmation bias) but give you the wrong impression.

Credible sourcing is the best detection tool

You’ll notice that our suggested counters to deep doubt above do not include watermarks, metadata, or AI detectors as ideal solutions. That’s because trust does not inherently derive from the authority of a software tool. And while AI and deepfakes have dramatically accelerated the issue, bringing us to this new “deep doubt” era, the necessity of finding reliable sources of information about events you didn’t witness firsthand is as old as history itself.

Since Stable Diffusion’s debut in 2022, we’ve often discussed the concerns surrounding deepfakes, including their potential to erode social trust, degrade the quality of online information by introducing noise, fuel online harassment, and possibly distort the historical record. We’ve delved deep (see what I did there) into many aspects of generative AI, and to date, reliable AI synthesis detection remains an unsolved issue, with watermarking technology frequently considered unreliable and metadata-tagging efforts not yet broadly adopted.

Further Reading

Why AI writing detectors don’t work

Although AI detection tools exist, we strongly advise against using them because they are currently not based on scientifically proven concepts and can produce false positives or negatives. Instead, manually looking for telltale signs of logical inconsistencies in text or visual flaws in an image, as identified by reliable experts, can be more effective.

It’s likely that in the near future, well-crafted synthesized digital media artifacts will be completely indistinguishable from human-created ones. That means there may be no reliable automated way to determine if a convincingly created media artifact was human or machine-generated solely by looking at one piece of media in isolation (remember the sermon on context above). This is already true of text, which has resulted in many human-authored works being falsely labeled as AI-generated, creating ongoing pain for students in particular.

Throughout history, any form of recorded media, including ancient clay tablets, has been susceptible to forgeries. And since the invention of photography, we have never been able to fully trust a camera’s output: the camera can lie. The perception of objective reality captured through a device is a fallacy—images have always been subject to selective framing, misleading context, or manipulation. Ultimately, our trust in what we see or read depends on how much we trust the source.

In some ways, the age of deep doubt stretches back into deep history. Credible and reliable sourcing is our most critical tool in determining the value of information, and that’s as true today as it was in 3000 BCE, when humans first began to create written records.

Listing image by rob dobi via Getty Images