“Events are weaving together quickly. The fate of the world shall be decided.”

Dragon Age: The Veilguard is as much about the world, story, and characters as the gameplay. Credit: EA

BioWare’s reputation as a AAA game development studio is built on three pillars: world-building, storytelling, and character development. In-game codices offer textual support for fan theories, replays are kept fresh by systems that encourage experimenting with alternative quest resolutions, and players get so attached to their characters that an entire fan-built ecosystem of player-generated fiction and artwork has sprung up over the years.

After two very publicly disappointing releases with Mass Effect: Andromeda and Anthem, BioWare pivoted back to the formula that brought it success, but I’m wrapping up the first third of The Veilguard, and it feels like there’s an ingredient missing from the special sauce. Where are the quests that really let me agonize over the potential repercussions of my choices?

I love Thedas, and I love the ragtag group of friends my hero has to assemble anew in each game, but what really gets me going as a roleplayer are the morally ambiguous questions that make me squirm: the dreadful and delicious BioWare decisions.

Should I listen to the tormented templar and assume every mage I meet is so dangerous that I need to adopt a “strike first, ask questions later” policy, or can I assume at least some magic users are probably not going to murder me on sight? When I find out my best friend’s kleptomania is the reason my city has been under armed occupation for the past 10 years, do I turn her in, or do I swear to defend her to the end?

Ars Video

How Lighting Design In The Callisto Protocol Elevates The Horror

Questions like these keep me coming back to replay BioWare games over and over. I’ve been eagerly awaiting the release of the fourth game in the Dragon Age franchise so I can find out what fresh dilemmas I’ll have to wrangle, but at about 70 hours in, they seem to be in short supply.

The allure of interactive media, and the limitations

Before we get into some actual BioWare choices, I think it’s important to acknowledge the realities of the medium. These games are brilliant interactive stories. They reach me like my favorite novels do, but they offer a flexibility not available in printed media (well, outside of the old Choose Your Own Adventure novels, anyway). I’m not just reading about the main character’s decisions; I’m making the main character’s decisions, and that can be some heady stuff.

There’s a limit to how much of the plot can be put into a player’s hands, though. A roleplaying game developer wants to give as much player agency as possible, but that has to happen through the illusion of choice. You must arrive at one specific location for the sake of the plot, but the game can accommodate letting you choose from several open pathways to get there. It’s a railroad—hopefully a well-hidden railroad—but at the end of the day, no matter how great the storytelling is, these are still video games. There’s only so much they can do.

So if you have to maintain an illusion of choice but also want to to invite your players to thoughtfully engage with your decision nodes, what do you do? You reward them for playing along and suspending their disbelief by giving their choices meaningful weight inside your shared fantasy world.

If the win condition of a basic quest is a simple “perform action X at location Y,” you have to spice that up with some complexity or the game gets very old very quickly. That complexity can be programmatic, or it can be narrative. With your game development tools, you can give the player more than one route to navigate to location Y through good map design, or you can make action X easier or harder to accomplish by setting preconditions like puzzles to solve or other nodes that need interaction. With the narrative, you’re not limited to what can be accomplished in your game engine. The question becomes, “How much can I give the player to emotionally react to?”

In a field packed with quality roleplaying game developers, this is where BioWare has historically shined: making me have big feelings about my companions and the world they live in. This is what I crave.

Who is (my) Rook, anyway?

The Veilguard sets up your protagonist, Rook, with a lightly sketched backstory tied to your chosen faction. You pick a first name, you are assigned a last name, and you read a brief summary of an important event in Rook’s recent history. The rest is on you, and you reveal Rook’s essential nature through the dialog wheel and the major plot choices you make. Those plot choices are necessarily mechanically limited in scope and in rewards/consequences, but narratively, there’s a lot of ground you can cover.

During the game’s tutorial, you’re given information about a town that has mysteriously fallen out of communication with the group you’re assisting. You and your companions set out to discover what happened. You investigate the town, find the person responsible, and decide what happens to him next. Mechanically, it’s pretty straightforward.

The real action is happening inside your head. As Rook, I’ve just walked through a real horror show in this small village, put together some really disturbing clues about what’s happening, and I’m now staring down the person responsible while he’s trapped inside an uncomfortably slimy-looking cyst of material the game calls the Blight. Here is the choice: What does my Rook decide to do with him, and what does that choice say about her character? I can’t answer that question without looking through the lens of my personal morality, even if I intend for Rook to act counter to my own nature.

My first emotional, knee-jerk reaction is to say screw this guy. Leave him to the consequences of his own making. He’s given me an offensively venal justification for how he got here, so let him sit there and stare at his material reward for all the good it will do him while he’s being swallowed by the Blight.

The alternative is saving him. You get to give him a scathing lecture, but he goes free, and it’s because you made that choice. You walked through the center of what used to be a vibrant settlement and saw this guy, you know he’s the one who allowed this mess to happen, and you stayed true to your moral center anyway. Don’t you feel good? Look at you, big hero! All those other people will die from the Blight, but you held the line and said, “Well, not this one.”

There’s no objectively right answer about what to do with the mayor, and I’m here for it. Leaving him or saving him: Neither option is without ethical hazards. I can use this medium to dig deep into who I am and how I see myself before building up my idea of who my Rook is going to be.

Make your decision, and Rook lives with the consequences. Some are significant, and some… not so much.

Your choices are world-changing—but also can’t be

Longtime BioWare fans have historically been given the luxury of having their choices—large and small—acknowledged by the next game in the franchise. In past games, this happened largely through small dialog mentions or NPC reappearances, but as satisfying as this is for me as a player, it creates a big problem for BioWare.

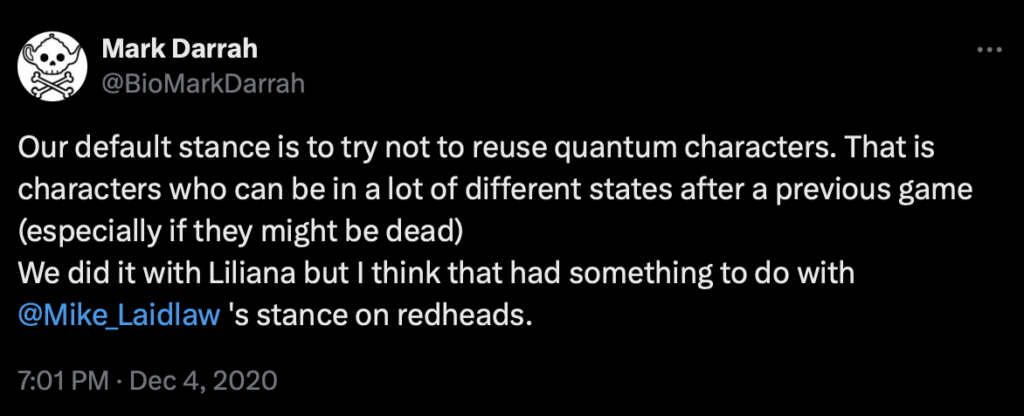

Here’s an example: depending on the actions of the player, ginger-haired bard and possible romantic companion Leliana can be missed entirely as a recruitable companion in Dragon Age: Origins, the first game in the franchise. If she is recruited, she can potentially die in a later quest. It’s not guaranteed that she survives the first game. That’s a bit of a problem in Dragon Age II, where Leliana shows up in one of the downloadable content packs. It’s a bigger problem in the third game, where Leliana is the official spymaster for the titular Inquisition. BioWare calls these NPCs who can exist in a superposition of states “quantum characters.”

If you follow this thought to its logical end, you can understand where BioWare is coming from: After a critical mass of quantum characters is reached, the effects are impossible to manage. BioWare sidesteps the Leliana problem entirely in The Veilguard by just not talking about her.

BioWare has staunchly maintained that, as a studio, it does not have a set canon for the history of its games; there’s only the personal canon each player develops as a result of their gameplay. As I’ve been playing, I can tell there’s been a lot of thought put into ensuring none of The Veilguard’s in-game references to areas covered in the previous three games would invalidate a player’s personal canon, and I appreciate that. That’s not an easy needle to thread. I can also see that the same care was put into ensuring that this game’s decisions would not create future quantum characters, and that means the choices we’re given are very carefully constrained to this story and only this story.

But it still feels like we’re missing an opportunity to make these moral decisions on a smaller scale. Dragon Age: Inquisition introduced a collectible and cleverly hidden item for players to track down while they worked on saving the world. Collect enough trinkets and you eventually open up an entirely optional area to explore. Because this is BioWare, though, there was a catch: To find the trinkets, you had to stare through the crystal eyes of a skull sourced from the body of a mage who has been forcibly cut off from the source of all magic in the world. Is your Inquisitor on board with that, even if it comes with a payoff? Personally, I don’t like the idea. My Inquisitor? She thoroughly looted the joint. It’s a small choice, and it doesn’t really impact the long-term state of the world, but I still really enjoyed working through it.

Later in the first act of The Veilguard, Rook finally gets an opportunity to make one of the big, ethically difficult decisions. I’ll avoid spoilers, but I don’t mind sharing that it was a satisfyingly difficult choice to make, and I wasn’t sure I felt good about my decision. I spent a lot of time staring at the screen before clicking on my answer. Yeah, that’s the good stuff right there.

In keeping with the studio’s effort to avoid creating quantum worldstates, The Veilguard treads lightly with the mechanical consequences of this specific choice and the player is asked to take up the narrative repercussions. How hard the consequences hit, or if they miss, comes down to your individual approach to roleplaying games. Are you a player who inhabits the character and lives in the world? Or is it more like you’re riding along, only watching a story unfold? Your answer will greatly influence how connected you feel to the choices BioWare asks you to make.

Is this better or worse?

Much online discussion around The Veilguard has centered on Bioware’s decision to incorporate only three choices from the previous game in the series, Inquisition, rather than using the existing Dragon Age Keep to import an entire worldstate. I’m a little disappointed by this, but I’m also not sure anything in Thedas is significantly changed because my Hero of Ferelden was a softie who convinced the guard in the Ostagar camp to give his lunch to the prisoner who was in the cage for attempted desertion.

At the same time, as I wrap up the first act, I’m missing the mild tension I should be feeling when the dialog wheel comes up, and not just because many of the dialog choices seem to be three flavors of “yes, and…” One of my companions was deeply unhappy with me for a period of time after I made the big first-act decision and sharply rebuffed my attempts at justification, snapping at me that I should go. Previous games allowed companions to leave your party forever if they disagreed enough with your main character; this doesn’t seem to be a mechanic you need to worry about in The Veilguard.

Rook’s friends might be divided on how they view her choice of verbal persuasion versus percussive diplomacy, but none of them had anything to say about it while she was very earnestly attempting to convince a significant NPC they were making a pretty big mistake. One of Rook’s companions later asked about her intentions during that interaction but otherwise had no reaction.

Seventy hours into the game, I’m looking for places where I have to navigate my own ethical landscape before I can choose to have Rook conform to, or flaunt, the social mores of northern Thedas. I’m still helping people, being the hero, and having a lot of fun doing so, but the problems I’m solving aren’t sticky, and they lack the nuance I enjoyed in previous games. I want to really wrestle with the potential consequences before I decide to do something. Maybe this is something I’ll see more of in the second act.

If the banal, puppy-kicking kind of evil has been minimized in favor of larger stakes—something I applaud—it has left a sort of vacuum on the roleplaying spectrum. BioWare has big opinions about how heroes should act and how they should handle interpersonal conflict. I wish I felt more like I was having that struggle rather than being told that’s how Rook is feeling.

I’m hopeful my Rook isn’t just going to just save the world, but that in the next act of the game, I’ll see more opportunities from BioWare to let her do it her way.