In 30th anniversary stream, Carmack and Romero recall a game dev “perfect storm.”

While Doom can sometimes feel like an overnight smash success, the seminal first-person shooter was far from the first game created by id co-founders John Carmack and John Romero. Now, in a rare joint interview that was livestreamed during last weekend’s 30th-anniversary celebration, the pair waxed philosophical about how Doom struck a perfect balance between technology and simplicity that they hadn’t been able to capture previously and have struggled to recapture since.

Carmack said that Doom-precursor Wolfenstein 3D, for instance, “was done under these extreme, extraordinary design constraints” because of the technology available at the time. “There just wasn’t that much we could do.”

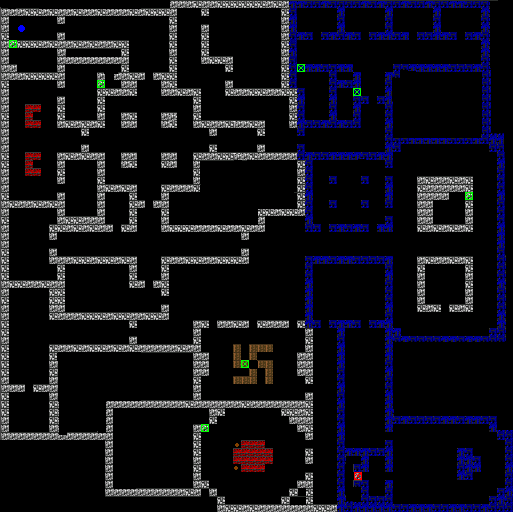

One of the biggest constraints in Wolfenstein 3D was a grid-based mapping system that forced walls to be at 90-degree angles, leading to a lot of large, rectangular rooms connected by long corridors. “Making the levels for the original Wolfenstein had to be the most boring level design job ever because it was so simple,” Romero said. “Even [2D platformer Commander Keen] was more rewarding to make levels for.”

By the time work started on Doom, Carmack said it was obvious that “the next step in graphics was going to be to get away from block levels.” The simple addition of angled walls let Doom hit “this really sweet spot,” Carmack said, allowing designers to “create an unlimited number of things” while still making sure that “everybody could draw in this 2D view… Lots of people could make levels in that.”

Romero expanded on the idea, saying that working on top of the Doom engine was, at the time, “the easiest way to make something that looks great. If you want to get anything that looks better than this, you’re talking 10 times the work.”Advertisement

Was Quake too complex?

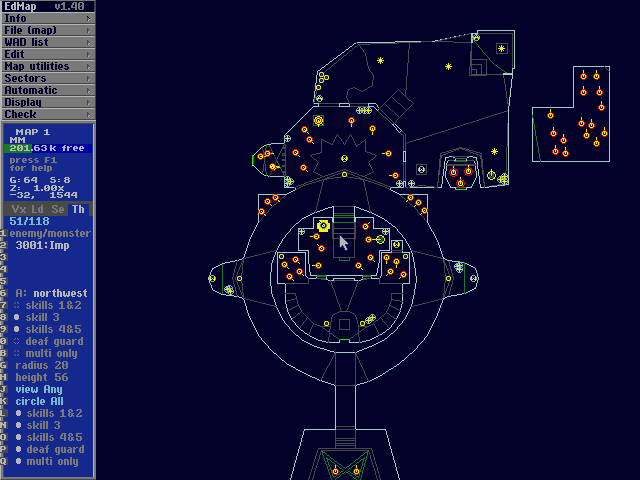

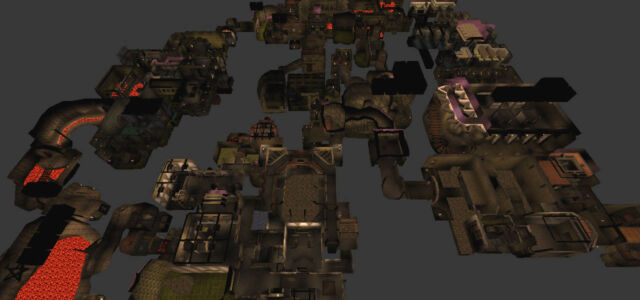

Then came Quake, with a full 3D design that Carmack admitted was “more ambitious” and “did not reach all of its goals.” When it came to modding and designing new levels, Carmack lamented how, with Quake, “a lot of potentially great game designers just hit their limit as far as compositional aesthetic in terms of what something is going to look like.”

“When you have the ability to do a full six degree-of-freedom modeling, you not only have to be a game designer, you have to be an architect, a modeler working through your composition,” Carmack continued. “[Doom] helped you along by keeping you from wasting time doing some crazy things that you would have had to be a master of a different craft to pull off… Going to full 3D made this something that not everybody does on a lark, but something you set out time, almost set a career arc to make mods for newer games.”

Romero reminisced during the chat about “the Everest of Quake” and “the insane amount of technology we took on” during its development. “Even adding QuakeC on top of [a] client/server [architecture] on top of full 3D, it was so much tech. It was a whole new engine, it wasn’t Doom at all. It was all brand new.”

Looking back, Carmack allowed that “there’s a couple different steps we could have taken [with Quake], and we probably did not pick the optimal direction, but we kept wanting to make this, just throw everything at it and say, ‘If you can think of something that’s going to be better, we should just strive our hardest to do that.’ When Doom came together, it was just a perfect storm of ‘everything went right.’.. [it was] as close to a perfect game as anything we made.”

Squashing the drama

During the roughly hour-long moderated livestream interview, Romero and Carmack generally avoided rehashing the drama of their storied professional breakup in the ’90s. Playing off the moderator’s mention of comparisons between id’s Carmack/Romero and the Beatles’ Lennon/McCartney, Carmack talked about the two Johns being treated as some of the first “rock stars” of the game development world and teased that Romero “leaned into it a little bit.”

Carmack remembered Doom‘s heyday as a time when “the world was fascinated with ‘video games are no longer this Atari 2600 that you plug into your TV.’ It suddenly looks cool enough for actual mainstream press to talk about. And any time the mainstream press is going to turn the ‘eye of Sauron’ on you, there’s going to be a focus on the interpersonal drama and figuring out everything else they can do to make an interesting or exciting story about it. It was almost inevitable.”

Romero, on the other hand, said the Lennon/McCartney comparison resonated for him because “I think we both spoke the same language because I also programmed. If you have a designer that can speak code, it’s a lot easier to know what to compromise on rather than coming up on a very unrealistic idea for a design thing. A lot of times, the designers don’t know what can be done, or even a simple feature could be really complex, but change a couple of words and we can do that right now.”

The beauty of “dumb” enemies

These days, Carmack spends most of his professional time in search of so-called artificial general intelligence. But when it came to designing Doom 30 years ago, Carmack says he found making enemy AI dumber actually made for a better gaming experience.

“We could have made the enemies [in Doom] a lot smarter, even with the constraints we had back then,” Carmack said. But creating super-smart enemies “is not as good of an idea as people might think,” he added, because “the world has to feel like it revolves around the player for the types of games we were doing.”Advertisement

“There’s something to be said for exploring a game that exists with or without you, but the enemies [in Doom] are mostly there to have an effect on the players, not to efficiently do something and not to go about their lives,” Carmack said. “For the types of games we were doing, you don’t really want particularly smart enemies. You don’t want them to do pathologically dumb-looking things that break the player’s immersion in something. But you do not really want them picking a hiding spot [and] flanking the player from behind. That’s not the enjoyable thing.”

While some players might enjoy facing realistic, super-intelligent enemies, Carmack said he found that most players “want to go in and Rambo their way through everything, and that doesn’t take a whole lot of intelligence in the enemies.”

Romero agreed during the livestream that “having more of something dumb [on-screen] is better than having one super-smart AI,” a lesson that he urged developers to heed today. “People are still trying to push the envelope on having smarter enemies. Well, people are like, ‘That’s too smart,’ people want to turn it off. So I think we made the right decision in Doom with having enemies that moved how they did, which was typically pretty slow, but we had huge numbers of them, and that was more interesting because you had to be more strategic.”

But Carmack suggested that the state of modern AI technology could soon change that calculus for certain types of games. “We are approaching a new era with the way artificial intelligence stuff is going right now,” he said, “where the world of actual deep characters is going to be very different than it has been in the past years, where you can create something today that does have entire deep backstories that will, for certain types of games, be very transformative… AI stuff is definitely the future, but back then, I think we did make the right calls [for Doom].”

While Doom owes a lot of its longevity to its “sweet spot” simplicity, Romero also pointed to the 1997 release of the game’s source code as something that has “really made the game live [because] now it can be kept current on everything, it can now run on everything.”

FURTHER READING

Beyond emulation: The massive effort to reverse-engineer N64 source code

But Carmack lamented that Doom‘s openness to modification hasn’t been embraced by the wider industry. “You don’t see game companies release source code or even modding tools,” he said. “Reverse engineers have better tools… but it’s really not with the support of the studios, and that’s really a shame.”