FakeCall malware can reroute calls intended for banks to attacker-controlled numbers.

Credit: Getty Images

Researchers have found new versions of a sophisticated Android financial-fraud Trojan that’s notable for its ability to intercept calls a victim tries to place to customer-support personnel of their banks.

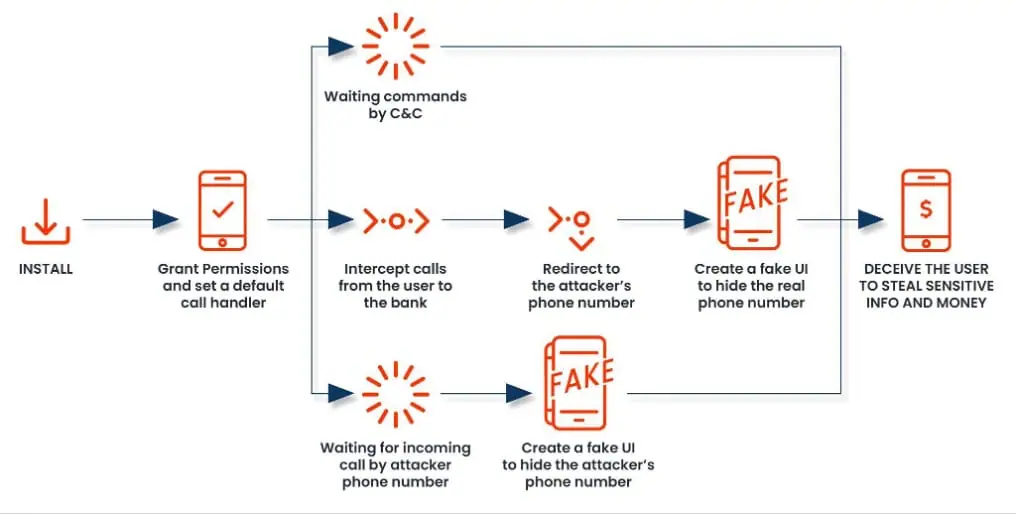

FakeCall first came to public attention in 2022, when researchers from security firm Kaspersky reported that the malicious app wasn’t your average banking Trojan. Besides containing the usual capabilities for stealing account credentials, FakeCall could reroute voice calls to numbers controlled by the attackers.

A strategic evolution

The malware, available on websites masquerading as Google Play, could also simulate incoming calls from bank employees. The intention of the novel feature was to provide reassurances to victims that nothing was amiss and to more effectively trick them into divulging account credentials by having the social-engineering come from a live human.

The interception was possible when victims followed instructions during installation to grant permission for the app to become the default call handler on the Android device. From then on, FakeCall could detect calls to a bank’s legitimate customer-support number and reroute them to an attacker-controlled number. To better hide the sleight-of-hand, the Trojan can display its own screen over the system’s.

On Wednesday, a researcher at mobile security firm Zimperium reported finding 13 new variants of the malware. The continued development of the already-sophisticated Trojan indicates the attackers behind it continue to ramp up investment in it.

“The newly discovered variants of this malware are heavily obfuscated but remain consistent with the characteristics of earlier versions,” Zimperium malware researcher Fernando Ortega wrote. Ortega continued: “This suggested a strategic evolution—some malicious functionality had been partially migrated to native code, making detection more challenging.”

Much of the new obfuscation is the result of hiding malicious code in a dynamically decrypted and loaded .dex file of the apps. As a result, Zimperium initially believed the malicious apps they were analyzing were part of a previously unknown malware family. Then the researchers dumped the .dex file from an infected device’s memory and performed static analysis on it.

“As we delved deeper, a pattern emerged,” Ortega wrote. “The services, receivers, and activities closely resembled those from an older malware variant with the package name com.secure.assistant.” That package allowed the researchers to link it to the FakeCall Trojan.

Many of the new features don’t appear to be fully implemented yet. Besides the obfuscation, other new capabilities include:

Bluetooth Receiver

This receiver functions primarily as a listener, monitoring Bluetooth status and changes. Notably, there is no immediate evidence of malicious behavior in the source code, raising questions about whether it serves as a placeholder for future functionality.

Screen Receiver

Similar to the Bluetooth receiver, this component only monitors the screen’s state (on/off) without revealing any malicious activity in the source code.

Accessibility Service

The malware incorporates a new service inherited from the Android Accessibility Service, granting it significant control over the user interface and the ability to capture information displayed on the screen. The decompiled code shows methods such as onAccessibilityEvent() and onCreate() implemented in native code, obscuring their specific malicious intent.

While the provided code snippet focuses on the service’s lifecycle methods implemented in native code, earlier versions of the malware give us clues about possible functionality:

- Monitoring Dialer Activity: The service appears to monitor events from the com.skt.prod.dialer package (the stock dialer app), potentially allowing it to detect when the user is attempting to make calls using apps other than the malware itself.

- Automatic Permission Granting: The service seems capable of detecting permission prompts from the com.google.android.permissioncontroller (system permission manager) and com.android.systemui (system UI). Upon detecting specific events (e.g., TYPE_WINDOW_STATE_CHANGED), it can automatically grant permissions for the malware, bypassing user consent.

- Remote Control: The malware enables remote attackers to take full control of the victim’s device UI, allowing them to simulate user interactions, such as clicks, gestures, and navigation across apps. This capability enables the attacker to manipulate the device with precision.

Phone Listener Service

This service acts as a conduit between the malware and its Command and Control (C2) server, allowing the attacker to issue commands and execute actions on the infected device. Like its predecessor, the new variant provides attackers with a comprehensive set of capabilities (see the table below). Some functionalities have been moved to native code, while others are new additions, further enhancing the malware’s ability to compromise devices.

The Kaspersky post from 2022 said that the only language supported by FakeCall was Korean and that the Trojan appeared to target several specific banks in South Korea. Last year, researchers from security firm ThreatFabric said the Trojan had begun supporting English, Japanese, and Chinese, although there were no indications people speaking those languages were actually targeted.

People should think long and hard about installing any mobile app, particularly for Android devices, which over the years have been a frequent target of Trojans promising one thing and delivering under the hood a host of malicious others. Apps that interface with financial institutions deserve more scrutiny still. Android users should also be sure to enable Play Protect, a service Google provides to scan devices for malicious apps, whether those apps were obtained from Play or from third parties, as the case is with FakeCall.

Zimperium has published indicators of compromise here.